I. Herbert A. Simon 1916~2001and Allen Newell 1927~1992II.《席勒 (Friedrich Schiller 1759~1805)與歌德 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1749~1832)》,是

2018年為紀念Herbert A. Simon的系列演講『益友系列: 友情五講 (及主要文獻根據 ) 2018年6月15日 』五主題之一,預計5月9日在漢清講堂錄影。

我在準備此題時,發現應該有一專題《Weimar-Jena 群英會 1795~1830》(日期只是暫定;Jena因有大學,是Weimar的知識份子的充電、靜養中心;歌德將"處理"Jena大學哲學家費希特的文件,都銷毀......表示不得已的"苦衷",後人不必費心猜測.......):

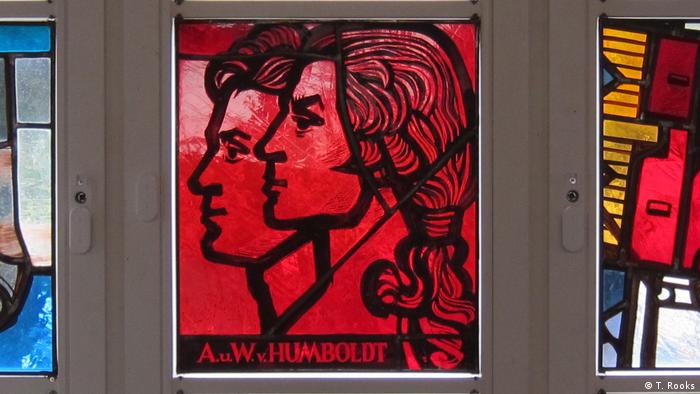

我們可以找到一張4人畫像:Goethe, Schiller, von Humboldts in Jena, c. 1797

更確切地講,題目是"Schiller, Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt with Goethe in Jena".

von Humboldts 者,即是著名的洪堡兄弟 (他兩幾乎都是通才:老哥叫Wilhelm von

Humboldt (1767~1835 ),是創建柏林大學的語言學家,他在1830年 (席勒沒後25年)整理語席勒的通信出版,並寫了長篇論文:On Schiller and the Course of His Spiritual Development by Wilhelm von Humboldt 1830. 接下來,也對歌德剛出版的《義大利之旅》評論,探討歌德的藝術觀。以上參考Stanford大學的哲學家網站:

Humboldt (1767~1835 ),是創建柏林大學的語言學家,他在1830年 (席勒沒後25年)整理語席勒的通信出版,並寫了長篇論文:On Schiller and the Course of His Spiritual Development by Wilhelm von Humboldt 1830. 接下來,也對歌德剛出版的《義大利之旅》評論,探討歌德的藝術觀。以上參考Stanford大學的哲學家網站:

In 1830 Humboldt edited and published his correspondence with the poet Schiller and included a lengthy essay “On Schiller and the Path of his Intellectual Development” (“Ueber Schiller und den Gang seiner Geistesentwicklung”, GS Vol 6: 492–527). In the same year appeared also an extensive essay on the late Goethe in the form of a review of the concluding part of the poet’s Italian Journeythat had been published the previous year. There he attempted, as he had done before in his Schiller essay, to interpret the various sides of the poet from one central point of view: this time from the poet’s perception of art and nature (“Rezension von Goethes Zweitem römischen Aufenthalt”, GS Vol 6: 528–550).

Art in its most basic sense is to be understood as the transformation of what is real into an image (Das Wirkliche in ein Bild zu verwandeln, GS Vol 2: 126, de transformer en image ce qui, dans la nature est réel”, GS Vol 1: 1). The art of the poet, more specifically, “consists in his ability or competence (Fertigkeit) to render the imagination creative according to rules”, to incite the imagination through the imagination (GS Vol 2: 127) and thereby create “a live act of communication” (lebendige Mitteilung) (GS Vol 2: 132). Among all the arts poetry occupies a special position in Humboldt’s view, because the material from which it is fashioned is not like ordinary material, as the stone or marble the sculptor uses, but instead consists of something already endowed with form, namely language. Poetry therefore “is art through language”. Through his imagination the poet creates works that represent “a world” embodying a totality of their own that differs in principle from the world of reality. In his definition of art Humboldt no longer looks at artworks as objects in order to gather from them a list of quasi objective qualities from which the nature of art could then be derived, but instead focuses on the process of aesthetic production and the rules by which it is governed and on how these rules are revealed in the poet’s art. In other words, a generative one has replaced the traditional mimetic or objective concept of art.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859)也是德國文化偶像 (他遊遍世界各地,對博物等很有心得,跟達爾文通信,說喜歡其祖父的植物詩歌.......)與歌德、席勒、貝多芬齊名。

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1749~1832 and Friedrich Schiller 1759~1805

- 作者: (德)呂迪格爾·薩弗蘭斯基

- 出版社:生活‧讀書‧新知三聯書店

- 出版日期:2017/01/01

- 語言:簡體中文

-----

我們可根據下篇加以補充:高秋福

歌德與席勒的友誼 下/

時間:2016-08-18 03:15:55來源:大公網

http://www.takungpao.com.hk/culture/text/2016/0818/17607.html

圖:歌德與席勒的棺木,至今仍然並排安放在一起/作者供圖

歌德與席勒的接觸更加頻繁,相知更加深透,他們不但相互競賽一般地寫詩,還創作小說和劇本。歌德在寫作小說《威廉.麥斯特的學習時代》的過程中,邊寫邊將手稿送給席勒閱讀。席勒閱後,坦誠地提出修改意見,令歌德深受感動。同時,他多次敦促歌德要盡早將史詩《浮士德》完成。歌德則建議席勒繼續戲劇創作,並答允劇本寫成後首先在他主管的宮廷劇院上演。戲劇創作之筆擱置近九年之後,席勒重新煥發出強烈的創作激情,於一七九九年完成以德國三十年戰爭為題材的歷史劇《華倫斯坦》三部曲。歌德當即將其第一部《華倫斯坦的營盤》安排上演。此後,席勒不顧病痛,又相繼完成《瑪利亞.斯圖亞特》、《奧爾良的姑娘》、《圖蘭朵,中國公主》、《墨西拿的未婚妻》、《威廉.退爾》等多部劇本。其中,以中國傳奇故事為題材創作的《圖蘭朵,中國公主》,是根據意大利劇作家戈齊(Carlo Gozzi)的原作,僅用兩個多月的時間就改寫完成的。為將這些劇本及時搬上舞台,歌德擔任榮譽導演和顧問,親自安排排演,甚至張羅服裝、選定音樂、分配角色。因此,人們後來說,歌德用自己的光輝照耀了席勒這個晚輩劇作家,促使德國戲劇事業走向復興和繁榮。

一八○五年四月末的一天,患有腎炎的歌德抱病前去探望纏綿病榻多日的席勒。席勒掙扎着從病榻上爬起來,堅持到劇院去看演出。歌德很高興,欣然陪同前往。豈料,這竟是兩位偉人最後一次晤面。五月九日晚,借藥物支撐着身體寫作的席勒,在離寫字枱不到兩步之遙的地方突然倒地,溘然長逝,年僅四十六歲。

hc案:5月11日 席勒 即出殯,歌德因病無法與會。

hc案:5月11日 席勒 即出殯,歌德因病無法與會。

歌德得悉摯友不辭而別,雙手蒙住眼睛,泣不成聲,他對友人說:「現在我失去了一位朋友,也失去了我生命的一半。」身陷巨大的悲痛,歌德幾個月不能正常寫作。直到八月十日,他才忍痛組織一次追悼會,會上演唱了席勒的著名詩篇《大鐘歌》。歌德為這首長詩撰寫了一首收場詩《席勒大鐘歌跋》。他在追懷席勒坎坷而輝煌一生的同時,稱頌他「向最高境界奮身追求」,創作了「許多豐富多彩的深刻作品,提高了藝術和藝術家的價值」。

hc案:

在英文,稱打油詩等"劣詩"為doggerel (ˈdɒɡ(ə)r(ə)l/)

noun

- comic verse composed in irregular rhythm.

"doggerel verses"- verse or words that are badly written or expressed.

"the last stanza deteriorates into doggerel"

例:He translated into wretched English doggerel Schiller's Das Lied von Der Glocke. (

Herbert Simon's Models of My Life, p.9)

他還把席勒(Schiller)的詩《大鐘歌》

《大鐘歌》很著名,可能全世界主要語種都有翻譯,十幾年前我讀過中文版,待查。YouTube 有全文朗誦,WIKIPEDIA的英文版有詳細說明:

Song of the Bell

席勒的遺體起初安葬在當時魏瑪唯一的公墓聖雅各教堂墓地。十多年後,魏瑪廢棄聖雅各教堂公墓,開闢現在稱為「歷史公墓」的新墓地。在被廢棄的亂墳岡中,人們後來發現二十多個顱骨。因為席勒身材高大,人們認定其中最大的一個必定屬於他。歌德聞訊,就將那個顱骨捧回家中暫時安放,隨後託人製作了一具橡木棺槨,於一八二七年十二月將亡友「那銘刻着神思奇想的顱骨」重新安葬。鑒於席勒在一八○二年獲封樞密顧問,榮升為貴族,這次被安葬在「歷史公墓」中的「公侯墓穴」。一八三二年三月二十二日,歌德病逝,根據他的身份和遺願,遺骸也安葬在「公侯墓穴」,與席勒長眠在一起。歷經一百八十多年的滄桑,我們現在看到,在幽暗的地下墓穴中,席勒與歌德的兩具同樣大小的棺木仍然並排安放在一起。不過,德國朋友相告,席勒的棺木中原來成殮的那塊顱骨,後來驗明不是他的,已被拿走。現在,他的棺槨實際上是空的。而在牆角下,擺放着一座他與歌德的半身雕像,二人比肩而坐,還像生前那樣親密。據說這是歌德生前特意安排的,表示他同席勒的友誼永世不渝。

席勒同歌德結交十年,兩人攜手合作,使德國文學達到前所未有的高峰。歌德與席勒這兩個光輝的名字,在文學史上,在億萬讀者的心目中,永遠連結在一起,密不可分。因此,前來陵墓拜謁的人終年不斷。他們用不同的語言呼喚着歌德和席勒的名字,殷殷情深。

Wilhelm von Humboldt - unwavering idealist

The last weeks have seen many commemorations to mark the 250th anniversary of Wilhelm von Humboldt's birth. He is known as a philosopher and linguist, but he was also a lover of nature and had a huge impact on science.

Though little remembered today outside of Germany, Wilhelm von Humboldt was an important Prussian statesman, thinker and scholar. Nonetheless, for him the name Humboldt was a double-edged sword and in old age he commented that he wished to be remembered as the "brother of the famous explorer," a clear reference to his well-known brother, Alexander.

Born in Potsdam in 1767 to a wealthy and well-connected family, Wilhelm and his younger brother were educated together by private tutors. Already in his early teens Wilhelm knew German, Greek, Latin and French. Later he would study Chinese, Tartar, Arabic and Coptic among a dozen other languages, and publish the first studies of the Basque and Kawi languages.

Home life was divided between a townhouse in central Berlin and summers at Schloss Tegel, a relatively small country house set in a large forest near a lake eight miles from the heart of Berlin. It was here that his love of nature began.

Friends and family

At the age of 20, Wilhelm finally entered the public school system by attending classes at the university in Frankfurt an der Oder before transferring to Göttingen. After a brief stint working in the Berlin court system he married Caroline von Dachröden with whom he eventually had eight children, five of which survived into adulthood.

Humboldt often had an authoritarian and chauvinistic relationship with women. The one great exception to this was his wife Caroline. She was his equal in every sense and flourished in her own right and became a patron of the arts

For the next ten years Humboldt had no fixed employment. He spent this time studying languages, and cultivating intimate friendships with polymaths Schiller and Goethe for whom he was an adept critic and supporter; the friendship with Goethe gave him new insights into the natural sciences.

When their mother died in 1796 Wilhelm and Alexander became truly independent. Wilhelm took over Schloss Tegel and other properties, while Alexander was satisfied with cash in order to pay for his planned trip around the world.

Though Wilhelm was now a man of the world with property to look after, it was still nature pure and simple that had his attention. He did not fanatically note barometric pressure or the height of mountain peaks like his brother, but he was nonetheless quite aware of his surroundings. His letters constantly mention clouds, the strength of storms, and above all trees.

Wilhelm von Humboldt's brother, Alexander, in his library in Berlin

In 1802, Wilhelm dutifully, yet reluctantly returned to state service and was sent to Rome to be Prussia's representative at the Vatican. These years were some of the family's happiest; but the Italian idyll was not to last. Another bigger task lay in front of Humboldt.

Prussian reforms

While Wilhelm was still in Rome, Napoleon was ravaging Europe. After he defeated Prussia in 1806, he marched into Berlin; Humboldt's own home was ransacked. In panic the Prussian king fled with his court and government to safety in the eastern-most part of his kingdom and settled in Königsberg.

Defeat meant that the country lost around half of its territory and population. It was also forced to pay a debilitating 120 million francs retribution to France, not to mention support 150,000 occupying French troops.

The dire situation of the country forced its leaders to begin a series of administrative, social and economic reforms. The idea was to keep Prussia afloat long enough for it to recoup and - if everything went well - to get back on the path to greatness.

The reforms touched nearly every part of life: the abolition of serfdom, the limitation of aristocratic power, and changes to the military, tax and education systems.

French occupiers left Berlin in December 1808, but the king stayed away for another year. Thus in Königsberg the government-in-exile went about its work transforming a state that hardly existed and where the outlook was anything but certain.

It was under these painful and precarious circumstances that Humboldt was put in charge of dealing with eduction and ecclesiastical affairs within the ministry of the interior. After three months preparation in Berlin, Humboldt joined the government in Königsberg where he spent the next eight months, before the government finally returned to the capital proper.

School system reform - the right place, the right time

By the time Wilhelm took up his job, some major decisions had already been made. Reformers were at the forefront and despite strained state finances had chosen to radically change elementary education throughout the country - or rather what was left of it.

No such measures had been put in place for secondary and higher education. Humboldt wasted no time getting to work. His plan was for a nation-wide three-tiered eduction system: integrating the already-changing elementary schools with secondary schools and a university based on humanistic values. General education was the key, while vocational and specialized professional training was to play a supplementary role.

Up to this point schools were typically under the jurisdiction of a town, patron or the church and teachers were often scarcely literate themselves. The nation needed to be reinvigorated and reimagined. It was essential to improve secondary schools; their focus going forward would be on teaching pupils how to learn.

To ensure success Humboldt implemented standardized instruction and state examinations for teachers, and installed a department within the ministry to oversee the creation of curricula and appropriate textbooks.

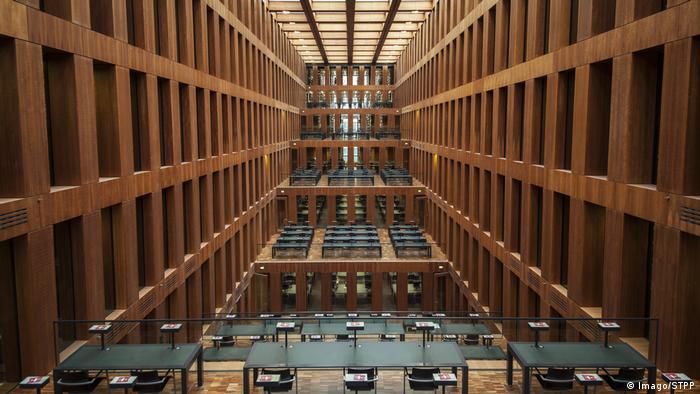

The University of Berlin - 'The classical German research university'

At the beginning of the 19th century Prussia already had some universities - in Königsberg and Halle for example. But Humboldt wanted something entirely different. His university would not be there to teach what was already known, but to grapple with questions whose answers are unknown. He called this search for answers “Wissenschaft” - the wholeness of knowledge.

Besides a unity of science and scholarship, his vision also included:

From 1828 until 1945 the school was known as Frederick William University. It was not until after the second world war that the name was changed to Humboldt Universtiy. Coincidently or not, statutes of the Humboldt brothers have been in front of the main campus building since 1883

He also saw many advantages to creating an entirely new school in Berlin; most important were the many independent institutes already in the city: the botanical garden, the observatory, the collections of natural history and art. This combination seems obvious today, but was revolutionary at the time and helped usher in a golden phase of research - especially in the natural sciences.

With this in mind and despite nearly empty state coffers, the University of Berlin was founded under the auspices of King Frederick William III in 1809 and classes began in the autumn of 1810 with an all-male student body of 256. The state took over all the running expenses.

When the university was founded women were not allowed in; they would have to wait until 1908 for the right to matriculate. Now there are over 34,000 students from around the world, well over half of whom are women

Back to nature at Tegel

After 16 months in office, Humboldt resigned in 1810. Yet he continued to serve Prussia and was appointed ambassador in Vienna and spent the next years negotiating various difficult treaties within Europe after Napoleon was finally stopped.

Prussia rebounded in size, population and importance. The reforms were starting to pay dividends and would eventually lead to a unified Germany - and with it the spread of Prussian ideas.

Finally in 1820, Humboldt's time in government came to an end. After a 17-year public career with extensive travel and having lived in Berlin, Jena, Paris, Rome, Vienna and London, the 52 year old was ready to retire. After transforming his childhood home into a small neoclassical palace, he lived on the shore of Tegeler See for the rest of his life.

Before moving into his childhood home, the house was transformed by Prussia's greatest architect and designer, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. After fours years of reconstruction, the once quaint home was turned into a neoclassical castle

Here he found a renewed interest in nature, took daily walks and enjoyed his gardens, vineyards and his trees.

It was also at Tegel that Humboldt wrote over a thousand sonnets.

Many of these short poems are dedicated to nature and have titles like: The Ocean; Clouds, Dreams, Songs; The Comet; Clouds and Stars; The Oak; The Soul of Plants; Water and Fire; or simply “Nature.”

"He was at his best as a writer when nature, in one or the other of its innumerable manifestations, was his subject," wrote Humboldt scholar Paul R. Sweet. "But he did not have Goethe's aptitude, which he so admiringly had described, for looking at nature with the eye of the scientist. Humboldt valued natural phenomena, not for their objective substance, but for the moods and feelings that they roused within himself."

In 1829, Wilhelm's wife Caroline died at the age of 63. With his eyesight failing, Humboldt lived another six years in relative seclusion and died on April 8, 1835 at his beloved Tegel.

Amazingly, Alexander lived another 24 years, dying in 1859 at the astounding age of 89.

A universal view

To his credit, Wilhelm like his brother, stuck to liberal principles his whole life. After seeing the direct aftermath of the French Revolution he pushed for a more representative government and restrictions on aristocratic privilege. He championed freedom of the press, due process and social mobility for all citizens regardless of family background.

Yet surprisingly many of his most significant writings that we know today were unpublished fragments when he died, all unavailable to his contemporaries. It was his daughter Gabriele and his brother Alexander who guarded his legacy, organized his papers and published many volumes of his work.

"In an age which often used the term 'universal' when it meant Europe, Humboldt was truly universal in interest and outlook." He believe in "the intrinsic worth of every human personality... All cultures, advance and primitive, were appropriate to the attention of the historian. Universal history should be truly universal," wrote Sweet.

A system built to last

Today, Wilhelm is viewed in many different and often-conflicting ways. Some see him as a hero of the common man while others see a patrician know-it-all who's utopian principles of education were too impractical even when they were conceived.

In any event the ideas behind the "Humboldtian model of higher education" are far more complex and nuanced than the highly simplified versions that are often (mis)quoted and (mis)used today.

Not only that, but as time wore on Humboldt's idea of Wissenschaft started to be understood as "specialized knowledge" rather than the "wholeness of knowledge." Universities were also once again subsequently becoming seen as places for practical professional training instead of the final stage in a general education.

As universities grew Humboldt's ideas did became too difficult to handle. The need for comparable qualifications and degrees made universities evolve, adding more rules and administrative layers.

Despite the fact that Berlin University developed in ways that diverged from what Humboldt had planned, it still became a model university. By the beginning of the 20th century, German universities were generally considered the best in the world. In the end, Wilhelm von Humboldt, the "other Humboldt" and unwavering idealist, must have done something right.

DW RECOMMENDS

- Date 05.07.2017

- Author Timothy Rooks

沒有留言:

張貼留言