Appraisal

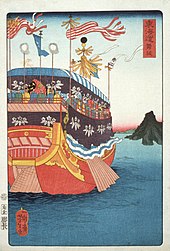

by Kunisada, 1863 誠實澄清月

。。。。

2023.6現在Google 不太一樣了,請用Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 試試便知

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsukioka_Yoshitoshi

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (Japanese: 月岡 芳年; also named Taiso Yoshitoshi 大蘇 芳年; 30 April 1839 – 9 June 1892) was a Japanese printmaker.[1]

Yoshitoshi has widely been recognized as the last great master of the ukiyo-e genre of woodblock printing and painting. He is also regarded as one of the form's greatest innovators. His career spanned two eras – the last years of Edo period Japan, and the first years of modern Japan following the Meiji Restoration. Like many Japanese, Yoshitoshi was interested in new things from the rest of the world, but over time he became increasingly concerned with the loss of many aspects of traditional Japanese culture, among them traditional woodblock printing.

By the end of his career, Yoshitoshi was in an almost single-handed struggle against time and technology. As he worked on in the old manner, Japan was adopting Western mass reproduction methods like photography and lithography. Nonetheless, in a Japan that was turning away from its own past, he almost singlehandedly managed to push the traditional Japanese woodblock print to a new level, before it effectively died with him.

His life was summed up by John Stevenson:

His reputation has only continued to grow, both in the West, and among younger Japanese, and he is now almost universally recognized as the greatest Japanese artist of his era.

Biography: The early years[edit]

Yoshitoshi was born in the Shimbashi district of old Edo, in 1839. His original name was Owariya Yonejiro. His father was a wealthy merchant who had bought his way into samurai status. At the age of three years, Yoshitoshi left home to live with his uncle, a pharmacist with no son, who was very fond of his nephew. At the age of five, he became interested in art and started to take lessons from his uncle. In 1850, when he was 11 years old, Yoshitoshi was apprenticed to Kuniyoshi, one of the great masters of the Japanese woodblock print. Kuniyoshi gave his apprentice the new artist's name "Yoshitoshi", denoting lineage in the Utagawa School. Although he was not seen as Kuniyoshi's successor during his lifetime, he is now recognized as the most important pupil of Kuniyoshi.

During his training, Yoshitoshi concentrated on refining his draftsmanship skills and copying his mentor's sketches. Kuniyoshi emphasized drawing from real life, which was unusual in Japanese training because the artist's goal was to capture the subject matter rather than making a literal interpretation of it. Yoshitoshi also learned the elements of western drawing techniques and perspective through studying Kuniyoshi's collection of foreign prints and engravings.

Yoshitoshi's first print appeared in 1853, but nothing else appeared for many years, perhaps as a result of the illness of his master Kuniyoshi during his last years. Although his life was hard after Kuniyoshi's death in 1861, he did manage to produce some work, 44 prints of his being known from 1862. In the next two years he had sixty-three of his designs, mostly kabuki prints, published. He also contributed designs to the 1863 Tokaido series by Utagawa School artists organized under the auspices of Kunisada.

The "Bloody Prints": capturing the public imagination[edit]

Many of Yoshitoshi's prints of the 1860s are depictions of graphic violence and death. These themes were partly inspired by the death of Yoshitoshi's father in 1863 and by the lawlessness and violence of the Japan surrounding him, which was simultaneously experiencing the breakdown of the feudal system imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate, as well as the effect of contact with Westerners. In late 1863, Yoshitoshi began making violent sketches, eventually incorporated into battle prints designed in a bloody and extravagant style. The public enjoyed these prints and Yoshitoshi began to move up in the ranks of ukiyo-e artists in Edo. With the country at war, Yoshitoshi's images allowed those who were not directly involved in the fighting to experience it vicariously through his designs. The public was attracted to Yoshitoshi's work not only for his superior composition and draftsmanship, but also his passion and intense involvement with his subject matter. Besides the demands of woodblock print publishers and consumers, Yoshitoshi was also trying to exorcise the demons of horror that he and his fellow countrymen were experiencing.

As he gained notoriety, Yoshitoshi was able to have ninety-five more of his designs published in 1865, mostly on military and historical subjects. Among these, two series would reveal Yoshitoshi's creativity, originality, and imagination. The first series, Tsūzoku saiyūki ("A Modern Journey to the West"), is about a Chinese folk-hero. The second, Wakan hyaku monogatari ("One Hundred Stories of China and Japan"), illustrates traditional ghost stories.

Between 1866 and 1868 Yoshitoshi created disturbing images, notably in the series Eimei nijūhasshūku ("Twenty-eight famous murders with verse"). These prints show killings in very graphic detail, such as decapitations of women with bloody handprints on their robes.[2] Other examples can be found in the strange figures of the 1866 series Kinsei kyōgiden, ("Biographies of Modern Men"), which depicted the power struggle between two gambling rings, and the 1867 series Azuma no nishiki ukiyo kōdan. In 1868, following the Battle of Ueno, Yoshitoshi made the series Kaidai hyaku sensō in which he portrays contemporary soldiers as historical figures in a semi-western style, using close-up and unusual angles, often shown in the heat of battle with desperate expressions.

It is said that Yoshitoshi's work of the "bloody" period has influenced writers such as Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (1886–1965) as well as artists including Tadanori Yokoo and Masami Teraoka. Although Yoshitoshi made a name for himself in this manner, the "bloody" prints represent only a small portion of his work.

The middle years: hard times and resurrection[edit]

By 1869, Yoshitoshi was regarded as one of the best woodblock artists in Japan. However, shortly thereafter, he ceased to receive commissions, perhaps because the public were tired of scenes of violence. By 1871, Yoshitoshi became severely depressed, and his personal life became one of great turmoil, which was to continue sporadically until his death. He lived in appalling conditions with his devoted mistress, Okoto, who sold off her clothes and possessions to support him. At one point they were reduced to burning the floor-boards from the house for warmth. It is said that in 1872 he suffered a complete mental breakdown after being shocked by the lack of popularity of his recent designs.

In the following year his fortunes turned, when his mood improved, and he started to produce more prints. Prior to 1873, he had signed most of his prints as "Ikkaisai Yoshitoshi". However, as a form of self-affirmation, he at this time changed his artist name to "Taiso" (meaning "great resurrection"). Newspapers sprung up in the modernization drive, and Yoshitoshi was recruited to produce "news nishikie". These were woodblock prints designed as full-page illustrations to accompany articles, usually on lurid and sensationalized subjects such as "true crime" stories. Yoshitoshi's financial condition was still precarious, however, and in 1876, his mistress Okoto, in a gesture of devotion, sold herself to a brothel to help him.

With the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, in which the old feudal order made one last attempt to stop the new Japan, newspaper circulation soared, and woodblock artists were in demand, with Yoshitoshi earning much attention. In late 1877, he took up with a new mistress, the geisha Oraku; like Okoto, she sold her clothes and possessions to support him, and when they separated after a year, she too hired herself out to a brothel. Yoshitoshi's works gave him more public recognition, and the money was a help, but it was not until 1882 that he was secure.

A series of bijin-ga designed in 1878 entitled Bijin shichi yoka caused political trouble for Yoshitoshi because it depicted seven female attendants to the Imperial court and identified them by name, it may be that the Empress Meiji herself was displeased with this fact and with the style of her portrait in the series.

Yoshitoshi published "Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan", a series of 51 works that depicted great men from Japanese mythology to the Edo period, from 1877 to 1882, and he further increased his reputation.[3]

In 1880, he met another woman, a former geisha with two children, Sakamaki Taiko. They were married in 1884, and while he continued to philander, her gentle and patient temperament seems to have helped stabilize his behaviors. One of Taiko's children, adopted as a son, became Yoshitoshi's student, and was thence known as Tsukioka Kōgyo.[1]

In 1883, Yoshitoshi published "Fujiwara no Yasumasa Gekka Roteki zu" (Fujiwara no Yasumasa Playing the Flute) an ukiyo-e, based on an original drawing which was exhibited at last year's exhibition of Japanese paintings. This work is based on setsuwa stories written in "Konjaku Monogatarishū" and "Uji Shūi Monogatari", which were compiled between the 12th and 13th centuries, and depicts a bandit, Hakamadare, trying to attack Fujiwara no Yasumasa who is playing the flute, but being unable to move because of Yasumasa's silent pressure. This work is regarded as one of Yoshitoshi's best.[4]

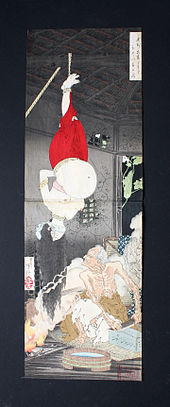

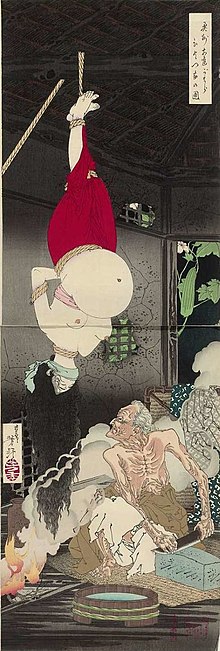

Yoshitoshi's notorious, yet compelling, "Oshu adachigahara hitotsuya no zu" (The Lonely House on Adachi Moor) appeared in 1885. This work depicts the legend of kijo in Kurozuka written in "Shūi Wakashū", which was compiled in the 11th century, and Kurozuka is also performed in noh, kabuki and jōruri.[5] This macabre work is iconic in its own right, and influential in the history of modern kinbaku, in that Itoh Seiu was fascinated by Yoshitoshi's accurate depiction of sakasa zuri (upside down suspension).

An 1885 issue of the art and fashion magazine "Tokyo Hayari Hosomiki" ranked Yoshitoshi as the number-one ukiyo-e artist, ahead of his Meiji contemporaries such as Utagawa Yoshiiku and Toyohara Kunichika. Thus he had achieved great popularity and critical acclaim.

By this point, the woodblock industry was in severe straits. All the great woodblock artists of the early part of the century, Hiroshige, Kunisada, and Kuniyoshi, had died decades earlier, and the woodblock print as an art form was dying in the confusion of modernizing Japan.

Yoshitoshi insisted on high standards of production, and helped save it temporarily from degeneracy. He became a master teacher and had notable pupils such as Toshikata Mizuno, Toshihide Migita, and others.

Later years: the eclipse of ukiyo-e[edit]

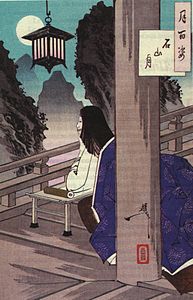

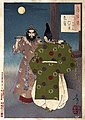

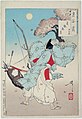

His last years were among his most productive, with his great series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892), and New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (1889–1892), as well as some masterful triptychs of kabuki theatre actors and scenes.

During this period he also cooperated with his friend, the actor Ichikawa Danjūrō, and others, in an attempt to preserve some of the traditional Japanese arts.

In his last years, his mental problems started to recur. In early 1891 he invited friends to a gathering of artists that did not actually exist, but rather turned out to be a delusion. His physical condition also deteriorated, and his misfortune was compounded when all of his money was stolen in a robbery of his home. After more symptoms, he was admitted to a mental hospital. He eventually left, in May 1892, but did not return home, instead renting rooms.

He died three weeks later in a rented room, on June 9, 1892, from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 53 years old. A stone memorial monument to Yoshitoshi was built in Mukojima Hyakkaen garden, Tokyo, in 1898.

Retrospective observations[edit]

During his life he produced many series of prints, and a large number of triptychs, many of great merit. Two of his three best-known series, the One Hundred Aspects of the Moon and Thirty-Six Ghosts, contain numerous masterpieces. The third, Thirty-Two Aspects of Customs and Manners, was for many years the most highly regarded of his work, but does not now have that same status. Other less-common series also contain many fine prints, including Famous Generals of Japan, A Collection of Desires, New Selection of Eastern Brocade Pictures, and Lives of Modern People.

While demand for his prints continued for a few years, eventually interest in him waned, both in Japan, and around the world. The canonical view in this period was that the generation of Hiroshige was really the last of the great woodblock artists, and more traditional collectors stopped even earlier, at the generation of Utamaro and Toyokuni.

However, starting in the 1970s, interest in him resumed, and reappraisal of his work has shown the quality, originality and genius of the best of it, and the degree to which he succeeded in keeping the best of the old Japanese woodblock print, while pushing the field forward by incorporating both new ideas from the West, as well as his own innovations.

Print series[edit]

- One Hundred Stories of Japan and China (1865–1866)

- Biographies of Modern Men (1865–1866)

- Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verses (1866–1869)

- One Hundred Warriors (1868–1869)

- Biographies of Drunken Valiant Tigers (1874)

- Mirror of Beauties Past and Present (1876)

- Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan (1876–1882)

- A Collection of Desires (1877)

- Eight Elements of Honor (1878)

- Twenty-Four Hours with the Courtesans of Shimbashi and Yanagibashi (1880)

- Warriors Trembling with Courage (1883–1886)

- Yoshitoshi Manga (1885–1887)

- One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892)

- Personalities of Recent Times (1886–1888)

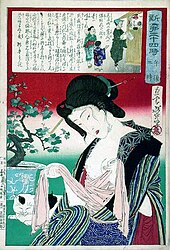

- Thirty-Two Aspects of Customs and Manners (1888) "Fuzoku sanjuniso – Aitasou"

- New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (1889–1892)

One Hundred Aspects of the Moon[edit]

Yoshitoshi's series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon consists of one hundred woodblocks, published in his later years, between 1885 -1892. Although some prints do not depict the moon, it is a unifying motif for the whole series.

Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan[edit]

Yoshitoshi's series Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan consists of fifty-one woodblocks, published in his middle years, between 1877 -1882.

Notable artwork[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric. (2005). "Tsukoka Kōgyō" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 1000.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012). 28 Famous Murders. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00AGHJVOS

- ^ "Mirror of Famous Generals of Great Japan". Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World.

- ^ "Fujiwara no Yasumasa Gekka Roteki zu". Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World.

- ^ Kurozuka. Kotobank.

- ^ Stevenson, John (1992). Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon. San Francisco Graphic Society. p. 49. ISBN 0-9632218-0-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Eric van den Ing, Robert Schaap, Beauty and Violence: Japanese Prints by Yoshitoshi 1839–1892 (Havilland, Eindhoven, 1992; Society for Japanese Arts, Amsterdam) is the standard work on him

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQGLB8

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). 28 Famous Murders. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00AGHJVOS

- Shinichi Segi, Yoshitoshi: The Splendid Decadent (Kodansha, Tokyo, 1985) is an excellent, but rare, overview of him

- T. Liberthson, Divine Dementia: The Woodblock Prints of Yoshitoshi (Shogun Gallery, Washington, 1981) contains small illustrations of many of his lesser works

- John Stevenson, Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (San Francisco Graphic Society, Redmond, 1992)

- John Stevenson, Yoshitoshi's Women: The Print Series 'Fuzoku Sanjuniso' (Avery Press, 1986)

- John Stevenson, Yoshitoshi's Thirty-Six Ghosts (Weatherill, New York, 1983)

- John Stevenson, Yoshitoshi’s Strange Tales (Amsterdam. Hotei Publishing 2005).

月岡 芳年(つきおか よしとし、天保10年3月17日〈1839年4月30日〉- 明治25年〈1892年〉6月9日)は、幕末から明治中期にかけて活動した浮世絵師。姓は吉岡(よしおか)、後に月岡。本名は月岡 米次郎(つきおか よねじろう)。画号は、一魁斎 芳年(いっかいさい よしとし)、魁斎(かいさい)、玉桜楼(ぎょくおうろう)、咀華亭(そかてい)、子英(しえい)。最後は大蘇 芳年(たいそ よしとし)を用いた。

河鍋暁斎、落合芳幾、歌川芳藤らは歌川国芳に師事した兄弟弟子の関係にあり、特に落合芳幾は競作もした好敵手であった。また、多くの浮世絵師や日本画家とその他の画家が、芳年門下もしくは彼の画系に名を連ねている(後述)。

概説[編集]

歴史絵、美人画、役者絵、風俗画、古典画、合戦絵など多種多様な浮世絵を手がけ、各分野において独特の画風を見せる絵師である。多数の作品があるなかで決して多いとは言えない点数でありながら、衝撃的な無惨絵の描き手としても知られ、「血まみれ芳年」の二つ名でも呼ばれる。浮世絵が需要を失いつつある時代にあって最も成功した浮世絵師であり、門下からは日本画や洋画で活躍する画家を多く輩出した芳年は、「最後の浮世絵師」と評価されることもある。昭和時代などは、陰惨な場面を好んで描く絵師というイメージが勝って一般的人気(専門家の評価とは別)の振るわないところがあったが、その後、画業全般が広く知られるようになるに連れて、一般にも再評価される絵師の一人となっている。

生涯[編集]

※新暦導入以前(1872年以前)の日付は和暦による旧暦を主とし、丸括弧内に西暦(1582年以降はグレゴリオ暦)を添える。同年4月(4月)は旧暦4月(新暦4月)、同年4月(4月か5月)は旧暦4月(新暦では5月の可能性もあり)の意。

天保10年3月17日(1839年4月30日)、江戸新橋南大坂町(武蔵国豊島郡新橋南大坂町[現・東京都中央区銀座八丁目6番]。他説では、武蔵国豊島郡大久保[現・東京都新宿区大久保])の商家である吉岡兵部の次男・米次郎として生まれる。のちに、京都の画家の家である月岡家・月岡雪斎の養子となる(自称の説有り、他に父の従兄弟であった薬種京屋織三郎の養子となったのち、初めに松月という四条派の絵師についていたが、これでは売れないと見限って歌川国芳に入門したという話もある)。

嘉永3年(1850年)、12歳で歌川国芳に入門(1849年説あり)。武者絵や役者絵などを手掛ける。

嘉永6年(1853年)、15歳のときに『画本実語教童子教余師』に吉岡芳年の名で最初の挿絵を描く。同年錦絵初作品『文治元年平家一門海中落入図』(大判3枚続)を一魁斎芳年の号で発表。

慶応元年(1865年)に祖父の弟である月岡雪斎の画姓を継承、中橋に居住した。

慶応2年(1866年)には橘町2丁目に住し、同年12月から慶応3年(1867年)6月にかけて、兄弟子の落合芳幾と競作で『英名二十八衆句』を表す。これは歌舞伎の残酷シーンを集めたもので、芳年は28枚のうち半分の14枚を描く。一連の血なまぐさい作品のなかでも、殊に凄まじいものであった。明治元年(1868年)、『魁題百撰相』を描く。これは、彰義隊と官軍の実際の戦いを弟子の旭斎年景とともに取材した後に描いた作品である。続いて、明治2年(1869年)頃までに『東錦浮世稿談』などを発表する。この頃、桶町、日吉町に住む。

明治3年(1870年)頃から神経衰弱に陥り、極めて作品数が少なくなる。1872年(明治4年/明治5年)、自信作であった『一魁随筆』のシリーズが人気かんばしくないことに心を傷め、やがて強度の神経衰弱に罹ってしまう。翌1873年(明治6年)には立ち直り、新しい蘇りを意図して号を大蘇芳年に変える。また、従来の浮世絵に飽き足らずに菊池容斎の画風や洋風画などを研究し、本格的な画技を伸ばすことに努め、歴史的な事件に取材した作品を多く描いた。

1874年(明治7年)、6枚つながりの錦絵『桜田門外於井伊大老襲撃』を発表。芳幾の新聞錦絵に刺激を受け、同年には『名誉新聞』を開始、1875年(明治8年)、『郵便報知新聞錦絵』を開始。これは当時の事件を錦絵に仕立てたもの。1876年(明治9年)、南金六町に住む。

1877年(明治10年)に西南戦争が勃発し、この戦争を題材とした錦絵の需要が高まると、芳年自身が取材に行ったわけではないが、想像で西南戦争などを描いた。

1878年(明治11年)には丸屋町に住んでおり、天皇の侍女を描いた『美立七曜星』が問題になる。1879年(明治12年)に再び南金六町に戻り、さらに宮永町へ転居しているが、この時期、手伝いにきていた坂巻婦人の娘・坂巻泰と出会っている。 1882年(明治15年)、絵入自由新聞に月給百円の高給で入社するが、1884年(明治17年)に『自由燈』に挿絵を描いたことで絵入自由新聞と問題になる。また、『読売新聞』にも挿絵を描く。1883年(明治16年)、『根津花やしき大松楼』に描かれている幻太夫との関係も生じるが、別れ、翌1884年(明治17年)、坂巻泰と正式に結婚する。

1885年(明治18年)、代表作『奥州安達が原ひとつ家の図』などによって『東京流行細見記』(当時の東京府における人気番付)明治18年版の「浮世屋絵工部」、すなわち「浮世絵師部門」で、落合芳幾・小林永濯・豊原国周らを押さえて筆頭に挙げられ、名実共に明治浮世絵界の第一人者となる。この頃から、縦2枚続の歴史画、物語絵などの旺盛な制作によって新風を起こし、門人も80名を超していた。この年、浅草須賀町に移る。

1886年(明治19年)10月、やまと新聞社に入社、錦絵『近世人物誌』を2年継続して掲載する。

1888年(明治21年)、「近世人物誌」を20でやめ、錦絵新聞附録とする。この時期までに200人余りの弟子がいたといわれる。

その後、『大日本名将鑑』『大日本史略図会』『新柳二十四時』『風俗三十二相』『月百姿』『新撰東錦絵』などを出し、自己の世界を広げて浮世絵色の脱した作品を作るが、それに危機を覚えてか、本画家としても活躍し始める。『月百姿』のシリーズは芳年の歴史故事趣味を生かした、明治期の代表作に挙げられる。また、弟子たちを他の画家に送り込んでさまざまな分野で活躍させた。

1891年(明治24年)、ファンタジックで怪異な作品『新形三十六怪撰』の完成間近の頃から体が酒のために蝕まれていき、再び神経を病んで眼も悪くし、脚気も患う。また、現金を盗まれるなど不運が続く。5、6年暮らした浅草の自宅の家相がよくないと聞き、日本橋浜町に新築するため、本所亀沢町に仮寓する[3]。

1892年(明治25年)、新富座の絵看板を右田年英を助手にして製作するものの、病状が悪化し、巣鴨病院に入院する。病床でも絵筆を取った芳年は松川の病院に転じるが、5月21日に医師に見放されて退院。6月9日、東京市本所区藤代町(現・東京都墨田区両国)の仮寓(仮の住まい)で脳充血のために死亡した(享年54、満53歳没)。しかし、『やまと新聞』では6月10日の記事に「昨年来の精神病の気味は快方に向かい、自宅で加療中、他の病気に襲われた」とある。

芳年の墓は新宿区新宿の専福寺にある。法名は大蘇院釈芳年居士。1898年(明治31年)には岡倉天心を中心とする人々によって向島百花園内に記念碑(月岡芳年翁之碑)が建てられた。

画風・画題[編集]

江戸川乱歩や三島由紀夫などの偏愛のため「芳年といえば無惨絵」と思われがちであるが、その画業は幅広く、歴史絵・美人画・風俗画・古典画にわたる。近年はこれら無惨絵以外の分野でも再評価されてきている。師匠・歌川国芳譲りの武者絵が特に秀逸である。

もともと四条派の画家に弟子入りしたためか、本人の曰く「四条派の影響を強く受けた」肉筆画も手がけている。彼自身、浮世絵だけを学ぶことをよしとしなかったため、様々な画風を学んでいる。写生を重要視している。

芳年の絵には師の国芳から受け継いだ華麗な色遣い、自在な技法が見える。しかし、師匠以上に構図や技法の点で工夫が見られる。動きの瞬間をストップモーションのように止めて見せる技法は、昭和期以降に発展してきた漫画や劇画にも通じるものがあり、劇画の先駆者との評もある。

歴史絵・武者絵[編集]

『大日本史略図会』中の日本武尊や、1883年(明治16年)の大判3枚続『藤原保昌月下弄笛図』(千葉市美術館所蔵)など、芳年には歴史絵の傑作がある。明治という時代のせいか、彼の描く歴史上の人物は型どおりに納まらず、近代の自意識を感じさせるものとなっている。

美人画・風俗画[編集]

美人画・風俗画も手がけており、『風俗三十二相』でみずみずしい女性たちを描いた。

無惨絵[編集]

初期の作品『英名二十八衆句』(落合芳幾との競作)では、血を表現するにあたって、染料に膠を混ぜて光らすなどの工夫をしている。この作品は歌川国芳(一勇斎国芳)の『鏗鏘手練鍛の名刃(さえたてのうちきたえのわざもの)』に触発されて作られた。これは芝居小屋の中の血みどろを参考にしている。当時はこのような見世物が流行っていた。

芳年は写生を大切にしており、幕末の動乱期には斬首された生首を、明治元年(1868年)の戊辰戦争では戦場の屍を弟子を連れて写生している。しかし、想像力を駆使して描くこともあり、1885年(明治18年)に刊行された代表作『奥州安達が原ひとつ家の図』など、その一例と言える。責め絵(主に女性を縛った絵)で有名な伊藤晴雨は、この絵を見た後、芳年が多くの作品で実践するのと同じく実際に妊婦を吊るして写生したのか気になり、妻の勧めで妊娠中の彼女を吊るして実験したという。そうして撮った写真を分析したところ、おかしな点があったため、モデルを仕立てての写生ではなく想像によって描かれたという結論に達した。その後、芳年の弟子にこのことを話すと、弟子は「師匠がその写真を見たら大変喜ぶだろう」と答えたという。

その他の画題[編集]

月に対しては名前のせいもあって思い入れがあるようで、月の出てくる作品が多く、『月百姿』という100枚にもおよぶ連作も手がけている。これは芳年晩年の傑作とされる。幽霊画も『幽霊之図』『宿場女郎図』などを描いており、芳年自身が女郎の幽霊を見たといわれている。

作品[編集]

月岡芳年の画家としての活躍は21歳から54歳までの33年間である。晩年の弟子山中古洞の分析では、芳年の作品のテーマは約500ほどであり、同じテーマの作品を複数製作することも多く、なかには同じテーマで100点もの作品を作った例もある。そのために芳年の生涯での製作作数は1万にも及ぶと見られている。またそれ以外にも本、雑誌、新聞などの挿絵が無数にあり、多くの浮世絵作家の中でも三代豊国や葛飾北斎に次ぐ多作家であろうとされている[4]。

錦絵[編集]

- 「正清三韓退治図」大判3枚続 元治元年(1864年) 神戸市立博物館所蔵

- 『和漢百物語』 大判25枚揃 慶応1年

- 『美勇水滸伝』 中判揃物 慶応2年

- 『英名二十八衆句』 大判28枚揃 慶応2年‐慶応3年 芳幾と合作

- 『魁題百撰相』 大判65枚揃 慶応4年‐明治2年

- 『一魁随筆』 大判13枚揃 明治5年‐明治6年

- 「郵便報知新聞第五三二号」 大判 明治8年(1885年)北九州市立美術館所蔵

- 『大日本名将鑑』 大判51枚目録共52枚揃 明治10年‐明治15年

- 『芳年武者无類』 大判32枚揃 明治16年‐明治18年

- 『新撰東錦絵』 大判2枚続 23組 明治18年‐明治19年

- 『月百姿』 大判100枚揃 明治18年‐明治25年

- 「魯智深爛酔打壤五台山金剛神之図」大判縦2枚続 明治20年(1887年)

- 『風俗三十二相』 大判32枚目録共33枚揃 「遊歩がしたさう 明治年間妻君之風俗」など 城西大学水田美術館所蔵 明治21年

- 『新形三十六怪撰』 大判36枚揃 明治22年‐明治25年

その他作品は多数ある。

肉筆浮世絵[編集]

| 作品名 | 技法 | 形状・員数 | 寸法(縦x横cm) | 所有者 | 年代 | 落款・印章 | 備考 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 佐久間盛政羽柴秀吉を狙う(太閤記) | 著色 | 幕絵1枚 | 195.0x900.0 | 福富太郎コレクション資料室 | 1864年(元治元年)頃 | 款記「一魁齋芳年」/花押 | 甲府道祖神祭礼で使われた幕絵。 |

| 曝首図 | 紙本淡彩 | 専福寺 | 1863年(文久3年) | ||||

| 深夜の訪問図 | 絹本著色 | 浮世絵太田記念美術館 | |||||

| 雪中常盤御前図 | 絹本著色 | 浮世絵太田記念美術館 | |||||

| 国芳肖像 | 紙本著色 | 浮世絵太田記念美術館 | |||||

| 猿田彦図 | 絹本著色 | 千葉市美術館 | |||||

| 羽衣図 | 絹本著色 | 東京国立博物館 | |||||

| 幽霊図 | 絹本著色 | 福岡市博物館 | 顔が女性器の幽霊の絵 | ||||

| ま組消防隊 | 絵馬 | 赤坂氷川神社 | 1889年(明治12年) | ||||

| 不動明王図 | 絵馬 | 成田山資料館 | 1885年(明治18年) | ||||

| 藤原保昌月下弄笛図 | 絹本淡彩 | 1幅 | 140.8x78.7 | ウースター美術館[5] | 1882年(明治15年) | 第一回内国絵画共進会に出品 | |

| 堀川夜討図 | 絹本著色 | 1幅 | 84.x42.5 | ウースター美術館[6] | |||

| スサノオ図 | 絹本著色 | 1幅 | 82x45 | ウースター美術館[7] | |||

| 加藤清正像 | 紙本墨画 | 1幅 | 123.5x47.5 | ウースター美術館[8] | |||

| 頼朝石橋山合戦受難之図 | 絹本著色 | 1幅 | 88.4x29 | ボストン美術館[9] | 1887-88年(明治20-21年)頃 | 款記「芳年」 | |

| 南朝勤王家之図 | 絹本著色 | 1幅 | 110.8x40.9 | ボストン美術館[10] | 1887-88年(明治20-21年)頃 |

人柄[編集]

芳年は弟子に厳しかったが、同時に大変かわいがった。これからは洋画の時代だと見越し、何人もの弟子を洋画家に弟子入りさせている。そのため、彼の弟子に大成した人は少なくない。涙もろい人情家でもあり、三遊亭円朝の人情話を聞いてすすり泣いたという話もある。眼は大きいが怖くない人だと、当時子供であった鏑木清方には思われていた。依頼で佐倉惣五郎を描くことになった際、どうも上手くいかないためモデルとして弟子を数人がかりで実際に柱に縛り付けていたところ、来訪した知人が驚いて「助けてやってくれ」と頼むと「こいつは悪いことをしたので縛り付けている」と悪乗りをして言い返すという逸話があり、ユーモラスな人でもあったようである。にぎやかなお祭り好きで、話し上手でもあった。芳年は神経衰弱を患っていたことがよく知られているゆえに、病んでいるようなイメージが一般的にはある。それでも病の床で絵を描き続けた。

影響[編集]

芳年の門人には山中古洞、水野年方、稲野年恒、右田年英、山崎年信、山田年忠、金木年景、新井芳宗、中澤年章などがおり、水野の門人に鏑木清方、池田輝方など、その他多数がいる。特に鏑木清方は子供の頃から芳年の家に遊びにきており、清方からさらに、美人画の旗手伊東深水や新版画運動を代表する川瀬巴水などが出ている。彼らは挿絵画家や日本画家として活躍した。また、芥川龍之介、谷崎潤一郎、三島由紀夫、江戸川乱歩などの文士たちに愛された。芸術家では横尾忠則が芳年の影響を受けて画集を発売している。

脚注・出典[編集]

- ^ 他説では、武蔵国豊島郡大久保(現在の東京都新宿区大久保)。

- ^ 「藤原保昌月下弄笛図」 刀剣ワールド

- ^ 芳年『浮世絵師伝』井上和雄編、渡辺版画店、昭和6

- ^ 瀬木 1978, pp. 115–116.

- ^ http://vps343.pairvps.com:8080/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search@/239/title-desc?t:state:flow=5a0f8c05-3f85-4cae-b991-58b701accb6b Worcester Art Museum - Fujiwara no Yasumasa Playing the Flute by Moonlight (Fujiwara no Yasumasa gekka roteki zu)]

- ^ Worcester Art Museum - Night Attack on Horikawa Castle

- ^ Worcester Art Museum - Susansoo

- ^ Worcester Art Museum - Kato Kiyomasa

- ^ Minamoto no Yoritomo at the Battle of Ishibashi-yama _ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- ^ Warrior Loyal to the Southern Court _ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

参考文献[編集]

- 番町書房 編『血の晩餐―大蘇芳年の芸術』番町書房、1971年3月。ASIN B000J93EX2。

- 瀬木慎一 編『月岡芳年画集』講談社、1978年3月。ASIN B000J8QDUY。

- 日本浮世絵協会編 『原色浮世絵大百科事典』第2巻 大修館書店、1982年 ※103頁

- 吉田漱『浮世絵の見方事典』北辰堂、1987年7月。ISBN 4-89287-152-4。ISBN 978-4-89287-152-8。

- 横尾忠則、中山豊彦『芳年─狂懐の神々』里文出版、1989年4月。ISBN 4-947546-39-5。ISBN 978-4-947546-39-5。

- 稲垣進一 編『図説 浮世絵入門』河出書房新社〈ふくろうの本〉、1990年9月。ISBN 4-309-72476-0。新装版2011年2月

- 悳俊彦『月岡芳年の世界』東京書籍、1993年1月。ISBN 4-487-79074-3。復刊ドットコム、2010年7月 ISBN 4-8354-4534-1

- 悳俊彦 編『芳年妖怪百景』国書刊行会、2001年8月。ISBN 4-336-04202-0。

- 小林忠監修 『浮世絵師列伝』 平凡社<別冊太陽>、2006年1月 ISBN 978-4-5829-4493-8

- 岩切由里子編著 編『芳年 月百姿』東京堂出版、2010年9月。ISBN 978-4-490-20702-6。

- 堀川浩之 「仙台の浮世絵師・熊耳耕年の“月岡芳年塾入門記”」、国際浮世絵学会 『浮世絵芸術』 171号所収、2016

- 図録

- 『最後の天才浮世絵師 月岡芳年展』 作品解説・年譜 西井正氣、日本経済新聞社、1995年

- 『浮世絵最後の巨匠 月岡芳年展』も掲載論文が一部異なる他は同上。

- 『月岡芳年風俗三十二相』町田市立国際版画美術館、二玄社・謎解き浮世絵叢書、2011年。日野原健司解説

- 『月岡芳年和漢百物語』町田市立国際版画美術館、二玄社・謎解き浮世絵叢書、2011年。菅原真弓解説

- 『月岡芳年魁題百撰相』町田市立国際版画美術館、二玄社・謎解き浮世絵叢書、2012年。小池満紀子・大内瑞恵解説

- 『月岡芳年妖怪百物語』太田記念美術館、青幻舎、2017年。日野原健司・渡邉晃解説

- 『月岡芳年月百姿』太田記念美術館、青幻舎、2017年。日野原健司解説

関連文献[編集]

- 月岡芳年・丸尾末広・花輪和一共作『江戸昭和競作 無惨絵―英名二十八衆句』1988年リブロポートISBN 978-4845703128

- 『衝撃の絵師月岡芳年 幕末・明治を生きた最後の浮世絵師』新人物往来社、2011年

- 『月岡芳年 幕末・明治を生きた奇才浮世絵師』平凡社「別冊太陽 日本のこころ」、2012年

- 『月岡芳年 血と怪奇の異才絵師 傑作浮世絵コレクション』河出書房新社、2014年

- 平松洋 『最後の浮世絵師 月岡芳年』角川新書、2017年

- 加藤陽介解説 『鬼才月岡芳年の世界 浮世絵スペクタクル』平凡社<コロナ・ブックス>、2018年

- 菅原真弓 『月岡芳年伝 幕末明治のはざまに』中央公論美術出版、2018年

- 『画帖 月百姿』双葉社ムック、2018年

関連項目[編集]

外部リンク[編集]

- 「月岡芳年『月百姿』」 『美の巨人たち』 テレビ東京、2010年7月30日放送回。 - “月岡芳年「月百姿」”. 美の巨人たち(公式ウェブサイト). テレビ東京 (2010年7月30日). 2011年11月23日閲覧。

- 月岡芳年コレクション(435点) - ロサンゼルス・カウンティ美術館所蔵